Wellness Takes on Overtourism

Worldwide, more than 1.3 billion people travel internationally annually, up from 500 million trips in 1995. The problem is, they all want to see the Mona Lisa.

By Laural Powell with Beth McGroarty

The good news is that the world is becoming more affluent. The good and bad news is that increasing numbers of people are opting to spend their new-found wealth on travel. Worldwide, more than 1.3 billion people travel internationally annually, up from 500 million trips in 1995.

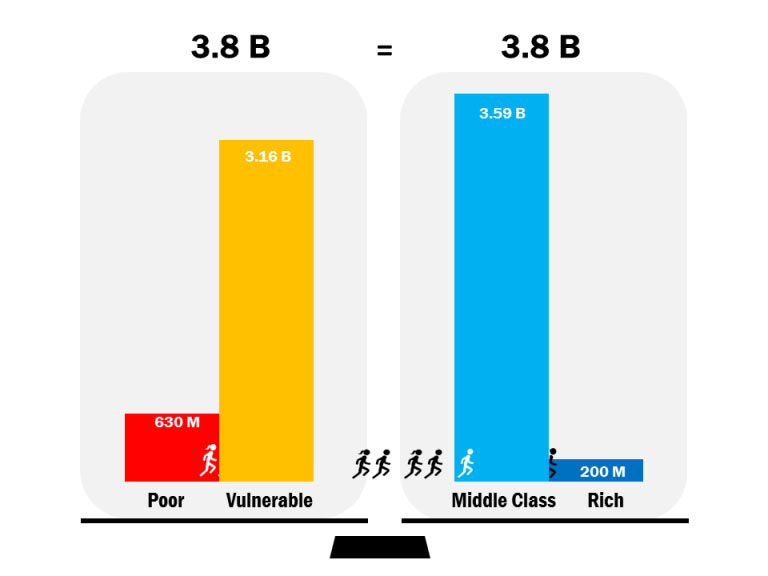

According to the Brookings Institution, “By our calculations, just over 50 percent of the world’s population, or some 3.8 billion people, live in households with enough discretionary expenditure to be considered middle class or rich.” Additionally, “the rate of increase of the middle class, in absolute numbers, is approaching its all-time peak. Already, about 140 million are joining the middle class annually and this number could rise to 170 million (per year) in five years’ time.

That explosion is a double-edged sword. If greater wealth leads to a growing ability to travel, then, in theory, more places could benefit economically from tourism. The trouble, however, is that the tourism expansion happens to be highly concentrated. According to Euromonitor International, 46 percent of all travelers go to just 100 destinations.[1]

Gloria Guevara, the CEO of the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC), warns of the problems caused by that concentration. “The top 20 country destinations will add more arrivals by 2020 than the rest of the world combined. Places (that) capture a significant share of the travel and tourism pie…may be threatened by their own popularity in environmental, social, or aesthetic terms.”

This clustering of international travelers in a handful of countries is likely to continue. By 2020, Euromonitor projects the top 20 countries in its study will see an additional 121 million arrivals, while the remaining 59 countries will receive around 72 million arrivals. If those new tourists were distributed throughout various regions of the top countries, this might not be a problem. But many first-time globetrotters want to see the highlights—the Mona Lisa in Paris, the Ginza in Tokyo, the canals of Venice—meaning the preponderance of new travelers are treading familiar and crowded tourism routes.

In addition to an emerging middle class, other factors contributing to the recent exponential growth in international tourism include demographic shifts (those millennials love spending their money on experiences), the awareness of new emerging travel markets, convenience and improved connectivity, and travel options designed to fit a wide range of budgets. Again, while all of these factors democratize travel, which is good, they can also contribute to the growing problem of overtourism.

We’ve been hearing the term overtourism a great deal during the past two years. Headlines about its dangers are everywhere, from CNN to Condé Nast Traveler to Skift, a global travel intelligence company. An August 2016 Skift thought piece on the impact of too much tourism spurred the wave of awareness of the problem. By the end of 2017, the WTTC and McKinsey & Company had published “Coping with Success: Managing Overcrowding in Tourism Destinations.” The report studies how overcrowding threatens the world’s natural and cultural wonders. By 2018, the Oxford Dictionary had put overtourism on its annual “Word of the Year” list.

Fueling the Trend

Overtourism Defined

Overtourism is one of the most pressing issues impacting the travel and tourism industry today. This is especially the case in Europe, where the phenomenon is most acute.

One of the challenges in defining overtourism is that its symptoms vary across destinations. In cities, too many tourists can alienate residents and overtax local infrastructure. In UNESCO World Heritage sites like Machu Picchu and Angkor Wat, mass tourism leads to litter-filled landscapes, threatening the spiritual, cultural and physical integrity of sacred places. On the beaches of Thailand and the Philippines and Spain, overtourism damages the environment and degrades the visitor experience. On Easter Island; in Bagan, Myanmar; and in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, hordes of tourists pose threats to local heritage and culture. Regardless of the symptoms, the common denominator is a negative outcome—whether on the environment, on the local residents, on the culture, or on the tourism experience.[2]

In “Tackling the Problem of Overtourism,” academics Claudio Milano, Joseph M. Cheer and Marina Novelli define overtourism “as the excessive growth of visitors leading to overcrowding in areas where residents suffer the consequences of temporary and seasonal tourism peaks, which have enforced permanent changes to their lifestyles, access to amenities and general wellbeing. The claim is that overtourism is harming the landscape, damaging beaches, putting infrastructure under enormous strain, and pricing residents out of the property market.”[3]

Rafat Ali, CEO and founder of Skift, speaking at the 2018 Global Wellness Summit in Italy, calls overtourism “a potential hazard to popular destinations worldwide…the dynamic forces that power tourism often inflict unavoidable negative consequences if not managed well.”[2]

Barcelona, Venice and Dubrovnik are among the most-cited examples of overtouristed places. According to the McKinsey/WTTC report, “Alienated residents voice a number of concerns, including rising rents, noise, displacement of local retail, and changing neighborhood character. In Barcelona, one of the first cities to elect a mayor who ran on a platform of managing overcrowding, residents complain of rising rents (as landlords opt to rent apartments to AirBnB guests instead of locals), and rowdy tourists taking over the city center. In Venice, tourists are actually displacing locals. In just 30 years, the city’s population was cut in half, to 55,000 and locals continue moving to the mainland to escape the tourist influx.”[4]

The report adds, “Given that the infrastructure used by tourists is shared with essential non-tourism activities, such as commerce and commuting, visitors add to the wear and tear and create challenges in terms of energy consumption and waste management.”[4]

Overtourism isn’t necessarily equivalent to overcrowding. Places affected include remote islands and national parks. Even small numbers of visitors to these delicate ecosystems can result in large negative impacts in terms of pollution, overuse of natural resources, and harm to wildlife. For example, in both Thailand and the Philippines, some islands have been closed to tourists in order to alleviate harm to landscapes and coral reefs. The New Zealand government has limited full-trail hikers of The Milford Track—a 33-mile trail that winds through the South Island’s mountains and rainforests—to 90 per day during peak season. In 2018, the prefecture of Haute-Savoie in France started limiting the numbers of daily climbers on Mont Blanc.

Why Overtourism Resonates

For the past 20 years, the travel industry has tried, at varying times, to promote the concepts of ecotourism, sustainable tourism and responsible tourism. But because of their nebulous definitions, and their reliance on the voluntary goodwill of governments, businesses and tourists, sometimes against self-interest, none of these concepts took off. Why has overtourism been able to capture the public imagination in a way that its cousins haven’t? Perhaps, says Ali, it is because the simple portmanteau of overtourism “appeals to basic baser instincts of alarm and fear versus altruism. That makes the business case for understanding and managing tourism better than appealing to the altruism implied by a sustainability label. It puts a framework around the global tourism boom, which often leads to destructive consequences.”[2]

Certainly, the quality of life issues associated with overtourism make it more relatable to the average person. Rising rents in urban areas, pollution, overcrowded public transportation and noise are all experiences that the average city dweller can understand.

One of the solutions oft-cited for easing the ills of overtourism is to encourage visitors to circulate to other locations around a popular region or country. The McKinsey/WTTC report says, “Efforts to redistribute visitors geographically—a tactic we call “spreading”—(should occur) across existing sites and new destinations. Spreading can ease several of the challenges associated with overcrowding, from creating an even distribution of tourists to drawing tourists away from bottlenecks.”[4]

Destinations can pursue spreading by promoting lesser-known attractions and developing alternative tourism regions. For example, some countries and cities are shifting the focus of promotions away from their most-visited attractions and toward wellness routes. According to the Global Wellness Institute’s Global Wellness Tourism Economy report, “Governments are looking to wellness tourism to diversify their tourist sector, carve out a unique niche, reduce seasonality, combat overtourism in some cases, and bring more benefits to local communities. A small but considerable number of countries also focus on developing this sector as part of their national tourism development/marketing strategies. Worldwide, the number of countries that actively market some form of wellness tourism at the national level has grown from 65 in 2013 to more than 100 today.”[5]

A Dose of Wellness

Overtourism is a wellness issue for the world. After all, travel to overtouristed places is not a well experience for visitors nor for locals. As economist Thierry Malleret puts it, “In the same way that air pollution negatively impacts the wellness experience where one cannot breathe, will overtourism do the same in places where one cannot move?”

Can wellness tourism prove to be the antidote that eases the ills of overtourism? Experts say diversifying the tourism product helps relieve pressure on natural and cultural resources and achieves a more equitable distribution of tourism benefits for residents. Certainly, wellness assets provide a path toward diversification and distribution.

Wellness travel can draw visitors to under-visited regions. According to Malleret, “At the recent Global Wellness Summit, some speakers stated that much of the growth in wellness tourism could take place in underdeveloped countries and areas, thus providing an “escape valve” to the problem of overtourism (one very specific example was Italy’s South Tyrol, a high-growth wellness destination that might also provide an overflow to some of the crowds in Venice).”

According to GWI’s Global Wellness Tourism Economy report, “Wellness tourism growth is very much a tale of developing markets, with Asia-Pacific, Latin America-Caribbean, Middle East-North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa accounting for 57 percent of the increase in wellness trips since 2015. Over the past five years, Asia is the number one growth sector in both wellness tourism trips and revenues.”[5] Many countries have only recently begun thinking about how they can position themselves to attract wellness tourism. They are developing strategies in conjunction with assessing impacts on local communities, according to Katherine Johnston, senior research fellow at the Global Wellness Institute. Starting from this point, she says, “lends itself to a more sustainable model for communities. The thinking of wellness is evolving to not just what’s good for me, but what is this bringing to the country and region.”

Indeed, the “we” in wellness is an important aspect to consider. According to the GWI report, “In recent years, wellness travel has also been evolving from a focus on being experiential to being transformative. Much of this transformation is still centering on “Me.” However, GWI predicts that a “We” perspective will grow as our quest for wellbeing continues to evolve, and wellness travel will see a shift from a consumptive to a contribution mindset. Future wellness travelers will increasingly link personal transformation with the connections they make during travel and their impacts on the people and the places that they touch, so that wellness travel will become a more meaningful two-way exchange between the travelers and the destination, instead of a one-sided consumptive and commercial transaction. This consumer evolution, along with the development of wellness tourism, can play an important role in mitigating the negative impacts of overtourism in some popular destinations and regions. In a holistic wellness framework, being well and doing good are closely connected. We cannot be truly well if our communities and the environment around us are not well.”[5]

The wellness community is largely ahead of the curve in having its collective consciousness awakened to the possibilities of making more ethical choices. Wellness pilgrims are realizing that the health of the places they are visiting, and their impact upon that health, is an important consideration when seeking venues aligning with their ideals of wellness and sustainability.

Additionally, by nature, wellness travelers often venture to destinations far off the crowded, beaten path. Many holistic wellness journeys require travelers to connect with destinations through nature and local traditions. “When you have local healing or medical traditions, spiritual and other practices, it makes the whole experience more authentic,” according to Ophelia Yeung, senior research fellow at the Global Wellness Institute.

Aspects of the Trend

Tourism professionals must seize on the interest of wellness travelers seeking alternative destinations that provide hyper-local, transformational experiences. Tourism boards need to shift their focus from promotion to planning and management challenges in order to spread these visitors to alternative areas. Those destinations with a clear, long-term vision are the most likely to achieve sustainable growth and mitigate—or prevent—overcrowding.

According to the Global Wellness Tourism Economy report, “Tourism leaders should ask questions about their product strategy: What differentiated and unique products are required to meet the needs of target segments? Wellness offerings are being linked with their own natural and cultural assets. Like other forms of specialty travel, wellness travel is not a cookie-cutter experience. Every destination has its own distinct flavors, linked with its local culture, natural assets, foods. The more discerning wellness travelers are interested in what the destination offers that is different. These unique experiences can be built upon indigenous healing practices, native plants and forests, vernacular architecture, street vibes, culinary traditions, history and culture. Wellness is multidimensional, encompassing a large and diverse set of activities and pursuits.”[5]

According to the McKinsey/WTTC report, destinations should opt “to be selective about the tourists they attract, focusing more on the value of tourism rather than the number of visitors. These tourism authorities want to attract ‘good tourists,’ defined as those who respect the destination and contribute to the local economy.”[4] Wellness tourists certainly fall into that category.

National tourism bodies are taking notice of the wellness market. They are realizing that a focus on wellness can be a smart strategy for reducing the effects of overtourism while distributing the benefits of economic development across a country.

Here are some of the reactive and proactive government initiatives aimed at combating overtourism through wellness.

A Tale of Two Countries: Croatia and Slovenia

Dubrovnik, Croatia is oft-cited as ground zero of the overtourism phenomenon. In 2016 alone, the city’s walled old town, which is home to just over 1,000 people, hosted one million tourists, 800,000 of whom were cruise ship passengers (who spend significantly less money than overnight visitors). Eighty-five percent of all visitors to Croatia come to Dubrovnik, and most of those visits happen during the summer season. According to the Croatian National Tourist Board (CNTB), the country has been keen on “the adoption of decisions in the area of wellness tourism” as encompassed in the Tourism Development Strategy of the Republic of Croatia and the Action Plan for the Development of Health Tourism in Croatia, both of which were approved in 2014.

In Croatia, wellness tourism, which is considered to “mainly take place in hotels and health resorts,” is defined as a product group consisting of medical wellness and holistic wellness. According to CNTB, “Wellness tourism is certainly in the group of products by which Croatia wants to achieve a more balanced seasonal and geographical distribution of the tourist traffic, which in practice means a shift from a dominant image of a sun and sea destination (which results in a heavy concentration of tourist activity during summer months) and the affirmation of those parts of Croatia which are from the touristic point of view still less known, although they offer very attractive contents and a high quality tourist offer.”

For example, Croatia has plans to develop a Wellness & Spa Tourism Zone in Varaždinske Toplice, an area with centuries of tradition in health tourism. According to the government’s investment prospectus, “The aim of the integral project is to turn Varaždinske Toplice into the highest quality health tourism destination, which will enable top positioning on the market as a prime destination in continental health tourism.”[6]

While Croatia’s policies have largely been reactive, instated to take the pressure off Dubrovnik, nearby countries are tackling the threat of overtourism proactively before it becomes an issue. For example, the national tourism plan of Croatia’s neighbor Slovenia focuses on geographically dispersing visitors across the country.

According to Maja Pak, the director of the Slovenian Tourist Board, “Slovenia tells a green story. We are surrounded by greenery—towards the Alpine peaks, the green forests, the Adriatic, the Karst, the vineyards, and the Pannonian plains. Awareness of our responsibility to develop tourism in a sustainable manner has become a priority. The ‘overtourism’ phenomenon has definitely and decisively accelerated this.”

To better distribute tourism flows and to develop tourism beyond major tourist destinations, Slovenia has created four macro-regions, three of which are wellness-oriented. The Thermal Pannonian is an area filled with healing waters. The Mediterranean and the Karst take in sea, lakes and caves. The northern Alpine region encompasses the mountains. The capital city of Ljubljana and its surroundings make up the fourth region.

In dividing the country in this way, Slovenia is merely promoting assets that already exist. For example, the country is rich with thermal mineral springs. Today, natural spa resorts and wellness centers combine natural features, years of healing traditions, and contemporary medical approaches in wellbeing and health. The Slovenian Spas Association works with the government to showcase these key assets, which can drive tourism throughout the entire country.

The World’s Newest Wellness Destinations

Japan

Other countries are also recognizing the potential of wellness tourism for economic development. Japan is now the third largest wellness tourism destination in Asia in terms of total visitors.[5] Traditionally, most of those visitors have come from within Asia. However, recently, the tourism industry writ large has received substantial investments in preparation for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. They are in part designed to broaden Japan’s international appeal and to distribute its tourism flows. The Japan National Tourism Organization (JNTO) has been developing new tourism routes with wellness features in order to coax travelers away from the congested Kyoto-Osaka-Tokyo corridor. For example, Japan’s Dragon Route (or “Shoryudo”) winds through the Chubu region, which includes historic and cultural sites, natural landscapes (including Mount Fuji), and plenty of hot springs. According to the JNTO’s New York office, the village of Misugi, located in Mie Prefecture, is commencing a wellness travel initiative utilizing existing assets. Promoted features include stargazing, forest bathing and a beer onsen.

Meanwhile, high-end brands, including InterContinental, Hyatt and Marriott, are opening resorts in lesser-known (among international visitors) tourism destinations within the country. All are keen on capitalizing on the attraction of the traditional Japanese spa experience. For example, Beppu, on the southern island of Kyushu, is a renowned onsen retreat among the Japanese. The scenic area has more than 2,400 natural springs. With the 2019 opening of the ANA InterContinental Beppu Resort & Spa, the area is aiming to increase its international tourism numbers significantly. The Lake Biwa Marriott Hotel, located by Japan’s largest lake, is also designed as a wellness destination. The Park Hyatt Niseko Hanazono, slated to open in 2020 in one of Japan’s prime ski destinations, will also have a large wellness component.

Cities

Even in the world’s most crowded cities, people need a respite. It may seem counterintuitive to place a wellness hospitality property smack in the middle of a major metropolitan area. But the fact is, several of the world’s top wellness brands are moving beyond their roots in idyllic locations to set up shop in big cities. Aman is already in Tokyo; Six Senses recently opened in Singapore; and both wellness brands are coming to New York City in 2020. Kerzner International Holdings Limited recently announced it is evolving its One&Only portfolio to include One&Only Urban Resorts. The first will open in Dubai. Fivelements, which runs a Balinese eco-wellness resort, is launching a wellness day spa concept in Hong Kong. According to Andrew Gibson, co-founder of the Wellness Tourism Association, “These examples of new wellness ventures in urban locations are a result of the overwhelming global interest in wellness and the increasing evidence that being healthy is not a preserve for the wealthy.”

Each of the companies mentioned is approaching its urban strategy differently. Aman’s urban properties appear to operate more like standard hotels, albeit with large spas and other wellness components. According to Roland Fasel, COO of Aman, the city hotels are designed around the brand pillars of high-touch service, creating experiences that derive from the local DNA, a holistic wellness component, uncomplicated luxury and understated elegance, and generosity of space. The orienting ethos of it all, says Fasel, is the idea of welcoming people into a home, which applies whether a guest is in the middle of nowhere or smack dab in the core of the Big Apple.

According to a press release, “One&Only Urban Resorts will challenge the conventional city hotel. In a buzzing and busy city, a place to escape the bright lights is always needed, a place to unwind; all urban resorts will offer beautifully designed green spaces to provide a serene sanctuary year-round.” Each urban resort will house a One&Only Gym, cycle and yoga studios, and a spa that is open around the clock.

Six Senses’ city properties will offer creative wellness programming, including options for social wellness. According to Anna Bjurstam, vice president, spas and wellness at Six Senses, “For example, in Singapore, where space is more limited, it’s about designing an immersive experience throughout the hotel through the content we are creating.” In such properties, where space is tight, she says “wellness shows up in different ways.” For example, the Six Senses Duxton hosts a resident Chinese doctor, who provides complimentary consultations for guests. According to Six Senses CEO Neil Jacobs, Six Senses in Singapore will also be developing a restaurant menu with Chinese medicinal offerings.

But Six Senses New York will be wellness on steroids (to mix metaphors). The most revolutionary aspect of the New York property will be its attention to social wellness. “We are aspiring to tackle one of biggest threats to wellness—loneliness—by introducing our first Six Senses Place, where hotel guests and members can be part of a community,” Bjurstam said.

A dedicated member and guest-only space will include a bathhouse, a clinic, a shared work space, halls for wellness lectures and other events, and a restaurant. Members and guests will also have access to blood tests, biomarker testing and other scientific treatments. And of course, there will be a very large spa.

Meantime, Fivelements is developing a standalone urban retreat in Hong Kong’s Causeway Bay. Yoga & Sacred Arts retreat is expected to open in 2019. The center will feature holistic practices aimed at fostering self-exploration, mental and physical health, and overall wellbeing. Designed to cater to urban wellness tribes, it will offer an array of yoga and dynamic sacred arts practices, plant-powered nutrition, and integrative wellness programs. There will also be plenty of bespoke therapies, including bodywork, intuitive healing, energy work and wellness coaching.

The Future

As we have discussed, overtourism is rearing its ugly head throughout the world. But given the recent publicity surrounding the issue, governments, businesses and travelers are starting to take heed. In large part, wellness tourism can be part of the solution.

At the 2018 Global Wellness Summit, Dr. Jean-Claude Baumgarten, the former president and CEO of the World Travel & Tourism Council, stated that wellness tourism could “be a solution to overtourism, by diversifying an established destination’s tourism product” and opening up new areas that travelers might not have previously considered.

Resolving the problems involved with overtourism starts with a change of mindset for all stakeholders. Fortunately, the wellness community is, by nature, a mindful group. And where wellness and mindfulness are “dominant lifestyle values,” according to GWI senior research fellow Ophelia Yeung, changing behavior by encouraging ethical choices is possible.

Governments are increasingly recognizing that quantity over quality is not a winning proposition when it comes to attracting tourists. Pristine destinations like Bhutan and Botswana have long limited tourism numbers, and now other countries are starting to protect their natural sites with the same strategy. Governments are also realizing that less-visited regions and contemplative landscapes can be competitive wellness assets. The 2018 Global Wellness Economy Monitor points out that wellness can move visitors out of a country’s over-visited regions to rural areas.

For example, in Italy, South Tyrol and Emilia-Romagna are actively promoting their wellness features, which may, in part, help draw visitors away from the crowds of Venice, Florence and Cinque Terre.

Another promising factor is that millennials and their younger Generation Z cohorts are always looking for the next big thing…often on Instagram. Social media is a way for unknown places with small budgets to gain traction, especially among “tribes” with very specific interests, including wellness travel.

Endnotes

[1] EuroMonitor International, Top 100 City Destinations Ranking: WTM London 2017 Edition.

[2] Rafat Ali, “Future of Travel and the Risks of Overtourism,” (presentation, Global Wellness Summit, Cesena, Italy, October 2018).

[3] Claudio Milano, Joseph M. Cheer and Marina Novelli, “Tackling the Problem of Overtourism,” The Business Times, August 11, 2018.

[4] McKinsey & Company and World Travel & Tourism Council, “Coping with Success: Managing Overcrowding in Tourism Destinations,” (December 2017).

[5] Global Wellness Institute, Global Wellness Tourism Economy, (November 2018).

[6] Catalogue of Investment Opportunities: Republic of Croatia, (2017).

Copyright © 2018-2019 by Global Wellness Summit.

If you cite ideas and information in this report please credit “2019 Wellness Trends, from the Global Wellness Summit”.

For more information, email beth.mcgroarty@www.globalwellnesssummit.com.