In Wellness We Trust: The Science Behind the Industry

People increasingly want to separate the wellness wheat from the chaff, and more resources and platforms will help them do it.

By Richard Panek

“Nonsense[1].” “A false antidote[2].” “Snake oil[3].”

Google “wellness” and these pejoratives might be among the first adjectives you’ll find. And not without reason. Years of baseless claims about pseudo-scientific products have blurred the distinctions between legitimate wellness practitioners and the charlatans who threaten to give wellness a bad name.

Semantics, in fact, is part of the problem. Anybody can package a vaginal egg and call it “wellness,” just as anybody could peddle a miracle elixir as part of a “medicine show.” And in many ways, wellness is in its own Wild West phase. The industry has been ripe for a reckoning—a rigorous accounting, whether through intense media criticism, internal vetting, or outside regulation, all based on empirical supporting evidence. And now it’s come.

There’s a new sheriff in town: the wellness watchdog.

People increasingly want to separate the wellness wheat from the chaff, and more resources and platforms will help them do it.

MEDIA AS WELLNESS WATCHDOG

Nothing says “wellness” like goop, literally

Goop—Gwyneth Paltrow’s lifestyle website and product line that reportedly is worth $250 million—has become “the epicenter of the wellness industry,” according to Bloomberg News[4]. By attracting a disproportionate share of media coverage (due in part to the celebrity of its founder), goop has become nearly synonymous with the market identity it’s appropriated: a “wellness” brand.

“The beauty of the term ‘wellness’ is that it encompasses almost everything and can cost almost anything,” writes Eva Wiseman, life and style columnist for the Guardian, in an article highly critical of goop in particular and—as if the leap were natural—the wellness industry in general[5]. Jennifer Gunter, the OB-GYN who has made a second career out of wellness skepticism, first came to prominence in 2017 as a goop critic (“Dr. Jen Gunter Wants to Protect Your Vagina from Gwyneth Paltrow,” read the headline on a profile of her in Mother Jones[6]). But Gunter, too, has broadened her attacks, in best-selling books and as a columnist at the New York Times, to encompass what she calls Big Natural (as opposed to Big Pharma)[7].

The leap is somewhat understandable. With its high prices, its sometimes questionable (and in at least one case, actionable) claims, and its cult of personality, goop gives the Jen Gunters of the world plenty of valid ammunition.

But what are they at war with?

Exercise? Healthy food? A good night’s sleep? A sense of community? Stress reduction?

Presumably not. These five cornerstones of wellness have plenty of proof as contributing to a healthy lifestyle. Studies abound for the wide-ranging health benefits of each of these bedrock principles of wellness, from studies agreeing that sleep deprivation affects productivity, concentration and mood to those proving a healthy diet leads to greater longevity. Nothing—no pill or Big Pharma solution—has more evidence for its impact on health than these five pillars.

Call-out websites have begun to add nuance to the criticisms. Estée Laundry, which Refinery29 named the 2019 “Influencer of the Year[8],” is an anonymous Instagram collective that regularly takes on the misleading or outright false claims of influencers, brands and publications in the beauty industry. “Our goal is to inform and empower our followers,” someone(s) from the website told Glamour in a rare interview[9]. “Our fans have shown that they are not afraid to stand up to brands and vocalize their concerns.”

That kind of proactive fandom is what rocketed The Dream to the top spot on Apple Podcasts charts; in its first season, where it took on multilevel marketing schemes, it recorded 10 million downloads[10]. The target of the podcast, in its second season, is wellness: What is it? Who sells it? What’s actually based on truth? Episodes explore its more “bombastic” and “unfathomable” promises.

So, it’s not wellness itself that today’s callout culture is calling out. Instead, it’s the sense that, whatever the merits of wellness in principle or in fact, the industry hasn’t been policing itself.

Who’s minding the ($4.5 trillion) store?

INDUSTRY AS WELLNESS WATCHDOG

We know what the free market can do if left to its own devices—and as the wellness market has boomed in the last few years, those devices have tended to involve screens: evidence-free apps and websites, dark-money “likes” and “five-star” ratings, YouTube and Instagram “wellness influencers”-for-hire.

Many unscrupulous wellness providers don’t even pretend to offer scientific support for their claims. A 2019 paper in the peer-reviewed Current Addiction Reports surveyed 700 smoking-cessation apps and found only 30 that provided some form of evidence—and of those 30, only four provided evidence that was actually scientifically useful[11]. (Finding the one study that relies on a small sample size to reach a conclusion favorable to your product’s promises is a minor art.) Other studies have found that out of 20,000 mental health apps, only three or four percent cite actual medical evidence. Researchers at the University of Glasgow examined the UK’s top nine weight-management influencers— those who had at least 80,000 followers on at least one social media site—and found that just one provided credible information[12].

Such fly-by-nightness, of course, is hardly peculiar to the wellness industry. The history of commerce has shown that the free market lacks the financial incentive for self-accountability. But that same history also offers a corollary: The free market lacks the financial incentive for self-accountability… until it doesn’t.

In May 2019, CVS Pharmacy, the retail division of CVS Health, announced that it had completed third-party testing of all vitamins and supplements it sells online and in stores—more than 1,400 products from 152 manufacturers across 11 categories[13]. The purpose of the “Tested to Be Trusted” initiative is to let customers know that what they see on the labels is what they get, and what they get is free of certain additives and ingredients.

Will the “Tested to Be Trusted” program prove to be a harbinger of greater accountability or an anomaly in an era of little accountability? Hard to say. But if nothing else, it shows that of all the product categories in the pharmacy at this particular historical juncture, the bottom line of one category in particular—wellness—now depends on earning the public’s “trust.”

Even goop, in an attempt to shore up trust, has made some moves to align itself with more medical professionals and evidence: Integrative physicians such as Dr. Steven Gundry (who heads up the International Heart and Lung Institute) and Dr. Aviva Romm (an integrative women’s and children’s physician) are contributing doctors; goop’s installed a director of science and research who is a former Stanford professor and hired a lawyer to vet all claims on the site and a full-time fact-checker. Its website now features more evidence-backed, thoughtful discussions about health topics, conditions and disease treatment: For example, ““Understanding Multiple Sclerosis[14]” or ““The Power of the Mind and Other Cutting-Edge Research on the Placebo Effect[15].” goop notes that in its new Netflix show The Goop Lab (launched 1/24/20), “Many of the experts interviewed… are doctors and research scientists from leading medical institutions.” Critics will continue to attack the philosophies of goop’s medical advisors, while goop will continue to argue that it’s committed to “physicians who are interested in both Western and Eastern modalities” with “an open mind.” But the goop watchdogs (and there is a not-so-mini-industry now that analyzes every company move and claim) have led to some company self-policing and more attention to the evidence behind its claims and endorsements. Wellness watchdogs have a loud microphone now, and it works.

“The moment you step into the health and wellness arena,” says Sarah Greenidge, the founder of WellSpoken, a UK-based website, “you become a health information provider, whether you like it or not.” As the name WellSpoken suggests, Greenidge’s site addresses accuracy in communicating wellness to the public. A former health consultant herself, she says she was “pretty shocked” when she went freelance and first entered the wellness arena. What she discovered was “the absolute chasm” between the strict quality standards in medicine and pharmaceuticals and the lax or nonexistent restraints in wellness.

In an attempt to (in its words) “counter the pseudoscience that has become commonplace in the wellness industry,” WellSpoken offers certification for brands, as well as training and accreditation for communicators.

Questionable claims about wellness also motivated the founders of WellSet, a new company that is attempting to create a marketplace where potential clients can find reputable specialists in their communities. “That is literally why we started this company,” says Tegan Bukowski, co-founder and CEO, to counteract “a conflation of the spiritual and health, where you feel like you can’t address your nutrition without being this person who also believes in the power of healing crystals.”

GOVERNMENT AS WELLNESS WATCHDOG

In June 2019, US Senator Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut sent a letter to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC)[16]. The subject was a new fad in the wellness marketplace, one that had grown into a $62 million industry in virtually no time at all: teatox. The product—teas loaded with caffeine and laxatives—would supposedly help customers achieve the goals implicit in the names of some of the products that Blumenthal cited in his letter: “Flat Tummy Co.,” “Boo Tea,” “MateFit.”

“These teas,” Blumenthal’s letter said, “do not have any clinically demonstrated benefit, and some components of the tea can be downright dangerous[17].”

What was remarkable about Senator Blumenthal’s response wasn’t that a government official was exercising the right to oversight. It was that the oversight emerged so quickly and with such precision.

Teatox is symptomatic of a couple of the major challenges that wellness regulators face. One is that new subcategories keep popping up—subcategories in which a lack of “clinically demonstrated” benefits is almost to be expected. Prescribed medicines, of course, are subject to strict government oversight. But US authorities have usually taken a hands-off approach to dietary supplements—the category to which detox teas belong. The FDA doesn’t require that manufacturers prove that they work—or even that they’re safe[18]. Yet here was a US senator not only identifying a new subcategory of wellness but exercising a new urgency in monitoring its claims.

Even so, government oversight of wellness products is not always welcome by the public. For some consumers, a lack of verifiable information might even be a benefit; they can fill in the blanks on the label with the cure for whatever ails them. In the early 2000s, more than a million Europeans signed a petition opposing the EU’s effort to impose uniform standards on food supplements[19]. Such products are “a salesman’s dream,” wrote Amanda Mull on the Atlantic website in January 2020[20]. “When little is known, virtually anything can be passed off as possible.” The directive, nonetheless, went into effect.

The second way that the teatox phenomenon has been symptomatic of the challenges that wellness regulators face is the promotion of wellness products. The concept of “influencers” in a pre-Internet age would have been meaningless. Yet watchdogs are now getting paid to think about what the Kardashians are getting paid to think about—or at least what the Kardashians are getting paid to promote.

But which watchdogs? Government regulators, yes: In 2017, the FTC, for the first time, sent Reminder Letters to prominent social media influencers and marketers about the legal requirement of adhering to the facts[21]. But the responsibility for monitoring influencers also extends to trade organizations. The Advertising Standards Authority of Ireland, for instance, reminds opinionators that their online advocacy must match the language requirements on the EU register of nutrition and health claims[22]. The website for the US consumer advocacy group Truth in Advertising lists three thousand examples of dubious marketing of supplements and other wellness products.

The response of these oversight agencies might reflect a turning point in the regulation of the wellness industry toward a more formalized—and, therefore, a more consistent and reliable and empirical— model. One possible portent: In October 2019, the US Department of Agriculture published “interim final rules[23]” for domestic production of hemp, including the hemp by-product cannabidiol, or CBD—the explosively popular ingredient in gummies and juices in marijuana-friendly states… and in oils that might help you sleep and in wipes that might calm your nerves.

“How big a deal could this be?” wrote Forbes columnist Louis Biscotti. “Think about the end of Prohibition. The federal government is finally creating standards that could help create a national marketplace. That could help move CBD from the margins to the mainstream, adding security, safety and consistency to manufacturing[24].”

EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE AS WELLNESS WATCHDOG

In one of her New York Times columns, Jen Gunter characterized the wellness industry as being awash in “useless products and scientifically unsupported tests.”

Fair enough. But what if the products (and practices) were useful, and what if the science behind them was solid? The challenge today for advocates of legitimate wellness is to distinguish between wellness that is legitimate and wellness that is highly suspect. And one way to do that is to make sure scientific evidence is not just available but part of the conversation.

In anticipation of that demand, and to facilitate that process, the Wellness Evidence website, wellnessevidence.com, a part of the Global Wellness Institute platform, has undergone an upgrade.

“The wellness world was developed out of hotels and spas and resorts,” says Dr. Marc Cohen, one of the founders of the Wellness Evidence website. “I came out of the medical and the research world.” He has spent his career trying to reconcile traditional modes of research with mindfulness. One result was Herbs and Natural Supplements: An Evidence-Based Guide, a standard textbook now in its fourth edition. Another was a website. “Wellnessevidence.com,” Dr. Cohen says, “was to bridge those two worlds.”

The site dates to the more innocent era of 2011. Back then, says Dr. Kenneth R. Pelletier, a clinical professor of medicine and psychiatry at the University of California School of Medicine in San Francisco and another founder of wellnessevidence.com, “the spa world was beginning to realize that people demand evidence. It’s their health, it’s their wellbeing that’s at stake, and they want to know, ‘Am I paying all this money, taking all of this time and really deriving benefit for my health, my happiness, my heart, my cancer?’—whatever it is.”

Now the website’s mission has expanded beyond spas to involve every facet of the wellness industry, and its mandate has broadened from providing information to providing context. As Dr. Daniel Friedland, another co-founder of wellnessevidence.com, as well as the author of the 1998 seminal textbook Evidence-Based Medicine, says, “It clarifies the degree of certainty or uncertainty that supports decision-making moving forward”—for instance, where to devote wellness’ limited resources for research.

In terms of establishing its empirical, scientific credentials, wellness has always operated at a disadvantage. The wellness industry, at least for now, lacks the kinds of resources that allow Big Pharma to conduct clinical trials both among large populations and over long periods of time.

Which is not to suggest that mainstream medical research is impeccable or comprehensive. “Many people have assumed that the practice of medicine is always evidence-based,” says Dr. Friedland. But a study in Medical Care Research and Review in 2012, for instance, concluded that out of the three thousand medical treatments it investigated, only about a third indicated a net benefit, while the effectiveness of 50 percent—half the standard treatments in medicine—was unknown[25].

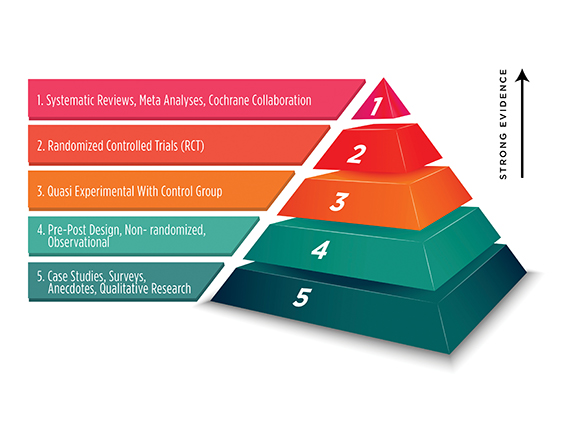

Nor is it to suggest that wellness research needs to rely on only gold-standard studies. Researchers, in general, rank reliable information on a scale from the exhaustive— meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials— to the anecdotal.

Nor is it to suggest that researchers within the wellness industry itself haven’t used clinical trials, longitudinal studies and other standard methods of evaluating medicine on an empirical basis. But contrary to Jen Gunter’s skepticism, useful products and practices do exist, and so does the science to support them.

But contrary to Jen Gunter’s skepticism, useful products and practices do exist, and so does the science to support them.

Wellnessevidence.com now offers 28 modalities—“alternative, integrative interventions,” says Dr. Pelletier—ranging from foundational topics such as exercise and weight loss through traditional alternative approaches such as acupuncture and meditation to more cutting-edge methods such as forest bathing and manual lymph drainage. Visitors to the website choose a topic from the modality menu and then explore it through four impeccable resources.

Three of those resources are ones that doctors often consult:

- The Cochrane Library, a collection of medical databases that contain, at its core, the Cochrane Reviews, which are extremely stringent systematic reviews and meta-analyses summarizing and interpreting the results of controlled trials;

- PubMed, a service of the US National Library of Medicine that offers a free digital archive of references and abstracts on life sciences and biomedical topics;

- The Trip Database, a metasearch engine that allows users to simultaneously search thousands of medical databases, medical publications and resources.

The fourth resource is Natural Standard, an international research collaboration that systematically reviews (and limits its focus to) scientific evidence on complementary and alternative medicine.

In effect, wellnessevidence.com offers direct access to the many thousands of studies (whether pro or con) for wellness approaches at the top databases, without filtering or editorializing. This portal is a way to enter the current wilderness of uncertainty and even scorn, stake a claim in the name of science and tame the frontier. Settlers welcome: wellness consumers, wellness manufacturers, wellness practitioners.

And, now more than ever, wellness watchdogs.

ENDNOTES

[1]We’ve Reached Peak Wellness. Most of It Is Nonsense by Brad Stulberg, Outside, 8 August 2019.

[2]Worshiping the False Idols of Wellness by Jen Gunter, the New York Times, 1 August 2018.

[3]The Mind, the Body and the Puzzle of Alternative Medicine by Lucinda Robb, the Washington Post, 25 January 2019.

[4]Goop Is Making a Killing Off Women Who Want More Than a Doctor’s Advice by Riley Griffin, Bloomberg, 18 March 2019.

[5]Is This the End of Wellness? by Eva Wiseman, the Guardian, 14 July 2019.

[6]Dr. Jen Gunter Wants to Protect Your Vagina from Gwyneth Paltrow by Maddie Oatman, Mother Jones, 23 August 2019.

[7]For So Long, Women Have Been Marginalized by Medicine by Lizzie O’Leary, the Atlantic, 27 August 2019.

[8]The Secret Instagram Group Airing the Beauty Industry’s Dirty Laundry by Rachel Lubitz, Refinery29, 13 November 2019.

[9]The Instagram Call-Out Revolution: A New Wave of Activist Accounts Are Coming for Brands and Influencers But Are They Trailblazers or Trolls? by Marie-Claire Chappet, Glamour, 24 December 2019.

[10]Jane Marie and Dann Gallucci’s ‘The Dream’ Podcast Investigates the Promises of a Booming Wellness Industry by Eric Ducker, the Los Angeles Times, 10 January 2020.

[11]So Many Health and Wellness Apps Haven’t Done Research to Back Up Their Claims by Rachel Kraus, Mashable, 18 June 2019.

[12]Many Wellness Brands Are Failing to Train the Influencers They Hire by Flora Tsapovsky, Healthyish, 2 October 2019.

[13]Press Release: CVS Pharmacy Launches ‘Tested to Be Trusted’ Program for Vitamins and Supplements, Launches Self-Care Campaign to Highlight Purpose-Led Initiatives and Expanded Product Assortment, CVS Pharmacy, 15 May 2019.

[14]Understanding Multiple Sclerosis, Goop, December 2019.

[15]The Power of the Mind and Other Cutting-Edge Research on the Placebo Effect, Goop.

[16]Senator Calls for FTC Investigation into ‘Dangerous Detox Teas’ on Social Media by Makena Kelly, The Verge, 4 June 2019.

[17]How Instagram and Government Officials Are Fighting the Aggressive Marketing of Weight Loss Products to Young Consumers, The Fashion Law, 11 October 2019.

[18]Dietary Supplements, US Food & Drug Administration, 16 August 2019.

[19]Controversial EU Vitamins Ban to Go Ahead by Sam Knight, Times Online, 12 July 2005.

[20]America Loves Its Unregulated Wellness Chemicals by Amanda Mull, the Atlantic, 1 January 2020.

[21]Press Release: FTC Staff Reminds Influencers and Brands to Clearly Disclose Relationship, Federal Trade Commission, 19 April 2017.

[22]Irish Influencers ‘Must Have Evidence’ to Back Up Their Instagram Claims about Wellness Products, TheJournal.ie, 7 May 2019.

[23]USDA Releases Highly Anticipated Interim Final Rule for Hemp Production, JD Supra, 8 November 2019.

[24]Feds Finally Crafting National CBD Rules by Louis Biscotti, Forbes, 15 November 2019.

[25]Half of Medical Treatments of Unknown Effectiveness by Austin Frakt, the Incidental Economist, 16 January 2013.

Copyright © 2019-2020 by Global Wellness Summit.

If you cite ideas and information in this report please credit “2020 Wellness Trends, from the Global Wellness Summit”.

For more information, email beth.mcgroarty@www.globalwellnesssummit.com.